The Circular Economy and the Value of Re-use: A case study

Emily Jones

Key Points

Global circularity must reach 17% to keep our planet within safer warming limits; current global circularity is about 7-8%.

Approximately 20 million functional but unused laptops and tablets are stored in households and SMEs.

The end of support for Microsoft Windows 10 poses an immediate risk of hundreds of millions of devices becoming obsolete in 2025.

Tech-Takeback converts obsolescence into a local opportunity, offering secure collection, GDPR-compliant data erasure, refurbishment, and local redistribution to individuals who are digitally excluded.

This example of circularity both conserves resources and has a significant social impact.

Why the Circular Economy Matters

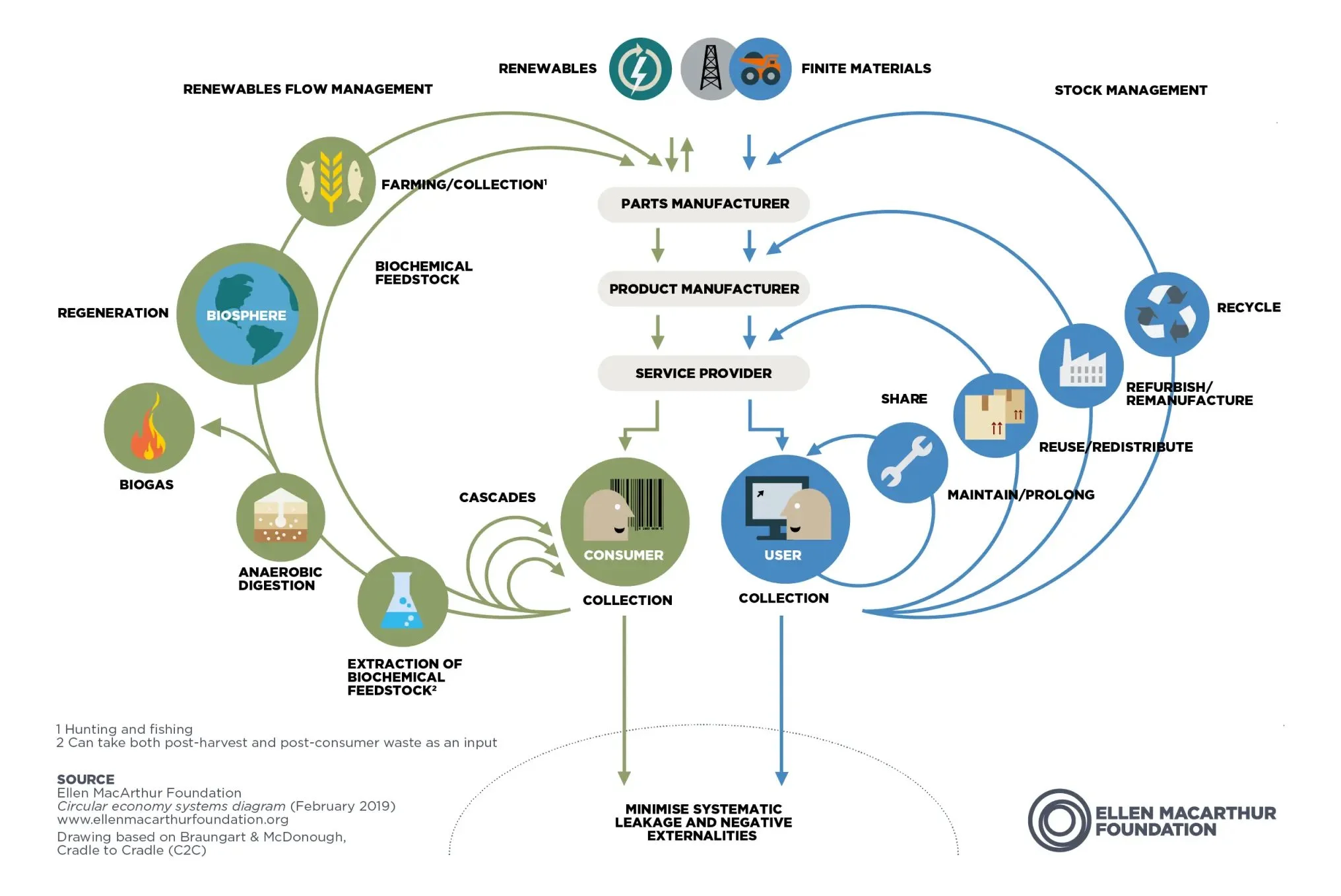

The circular economy offers a transformative alternative to the prevailing linear ‘take-make-waste’ model that has shaped economic activity since the Industrial Revolution. Circularity seeks to eliminate waste, extend the use of materials for as long as possible, and restore natural systems. It does this through strategies such as design for disassembly, produce-as-service models, remanufacturing, and closed-loop recycling (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2013; Bellini et al., 2024): see Figure 1.

Figure 1

Model of a circular economy

Source: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/circular-economy-diagram

Since the dawn of agriculture around 10,000 years ago, human numbers have increased from four million to eight billion, along with sharp rises in material demand (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2013). In ten years' time, resource demand is projected to grow by a further third as more people join the global middle class, causing an unprecedented surge in consumption. As American economist Daly (1987) pointed out, infinite economic growth cannot be sustained on a planet with finite resources. This reality stands in stark contrast to neoclassical development models that emphasise GDP growth, treating the economy as an abstract monetary system that is separate from Earth’s biophysical limits.

The Circularity Gap Report (2025) emphasises the need to reduce material consumption to 8.5 tonnes per capita, from over 12 tonnes per capita today, roughly the weight of two adult elephants per person, to reverse the overshoot of planetary boundaries. Furthermore, the European Commission notes that circular economies decrease environmental pressures by focusing on reusing materials and promoting resource efficiency. Transitioning to circular systems could cut greenhouse gas emissions by up to 70% and boost employment by around 4% across Europe (Stahel, 2016; Circular Economy Alliance, 2022).

Despite the potential, the global economy remains largely linear. In 2023, only 7.2% of global material flows were circular, meaning that over 90% of extracted resources were used once and discarded (Circle Economy, 2023). To stay within safe planetary boundaries and limit global warming to 1.6 °C by 2044, this circularity rate must increase to at least 17%.

Global, National, and Local Importance

At the global level, momentum towards circularity has been driven by landmark initiatives such as the European Union’s Circular Economy Action Plan, first introduced in 2015. This plan suggests measures to reduce the use of natural resources, cut waste, and incentivise reuse, refurbishment, and remanufacturing, marking a significant shift in economic strategy towards sustainability. More recently, the importance of circularity was underscored at COP30 Brazil, which, for the first time in history, hosted a dedicated Circular Economy Day on 11 November. These developments highlight the growing recognition of circular economy principles as central to sustainable economic development worldwide.

Nationally, the UK has begun to embed circularity into its economic planning. At the end of 2024, the government launched the Circular Economy Taskforce, an independent advisory group tasked with shaping England’s circular economy strategy. This strategy aims to facilitate economic growth, create skilled green jobs, promote efficient resource use, reduce consumer costs, and accelerate the transition to net-zero emissions. Complementing this, the West Midlands has developed a Circular Economy Routemap, guided by the Taskforce and supported by SOENECS, a Brighton-based research and innovation practice specialising in circular solutions. Importantly, these efforts align with existing legislation such as the Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012 and Procurement Policy Note (PPN) 06/20, which require public bodies to consider social and environmental outcomes in procurement. This integration of circularity with social value demonstrates how policy is increasingly designed to deliver not only environmental benefits but also wider societal impact.

Brighton and Hove is also preparing to update its own circular economy routemap, aiming to make it as comprehensive and informative as the West Midlands model. This update builds on the city’s established economic strategy, Productive, Inclusive, Transformative: An Economic Strategy for Brighton & Hove 2018 to 2023, which highlights sustainability and circularity as core priorities. A key driver of this vision has been extensive collaboration with local experts, including Circular Brighton & Hove, the University of Brighton, the University of Sussex, and SOENECS Ltd. One notable initiative is Circular Brighton and Hove’s Circular Businesses and Initiatives interactive map, which documents and promotes the city’s diverse ecosystem of sustainable businesses and organisations (Figure 2). The map highlights over 100 enterprises across various categories: consumer products and electronics; fashion; food and beverage; and manufacturing. It therefore provides a holistic view of how circularity is being integrated across sectors.

Figure 2

Circular Businesses and Initiatives in Brighton and Hove

Source: https://padlet.com/ecj2989/cbh-circular-businesses-and-initiatives-rrozrfuugtd0w2i2

As the city moves towards its route map update, this map exemplifies how locally driven tools can complement formal strategies, positioning Brighton & Hove as a leader in advancing circular economy practices at the city level.

The E-waste Crisis

Nowhere is the need for circularity more urgent than in the management of electronic (e-waste). The global demand for technology has surged, accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, yet it remains reliant on linear production models that encourage constant upgrades and planned obsolescence. E-waste, when improperly disposed of, significantly harms ecosystems and human health, and it also represents a huge loss of recoverable materials such as gold, silver, and copper. The planet produced 53.6 million metric tonnes of e-waste in 2019; a figure projected to rise to 74.7 million tonnes by 2030 (Good Things Foundation, 2023). The European Commission’s 2020 Circular Economy Action Plan established the Sustainable Product Policy to regulate single-use electronics and discourage planned obsolescence. However, nearly five years later, planned obsolescence persists and regulatory enforcement remains limited. In the United Kingdom alone, over six million tonnes of e-waste is generated each year, with only 17% being recycled.

Tech-Takeback: Local Circular Innovation in Action

Tech-Takeback was founded to revolutionise how society manages end-of-life electronics. It launched the UK’s first on-demand household collection service for electricals, enabling households and small businesses (SMEs) to donate unwanted devices securely. All data is erased in line with GDPR standards before devices are refurbished and redistributed within local communities. This method tackles a major barrier to device reuse identified by the Good Things Foundation (2023): the fear of data breaches among donors.

The end-of-support (EoS) date for Microsoft Windows 10, on 14 October 2025, highlights the ongoing issue of planned obsolescence. Ironically coinciding with International E-Waste Day, this change is expected to affect over 400 million devices worldwide. Windows 10 will no longer receive free security updates, technical assistance, or feature improvements, leaving users and their data vulnerable. Estimates suggest that as many as 240 million devices could be destined for landfill. Business Waste (2025) calculates this would amount to 12.8 million kilograms of recoverable metals: the weight of more than 8,500 cars.

In response, Tech-Takeback launched its Tech Amnesty Campaign in October 2025 to address the influx of end-of-support devices. The circular organisation offers free, secure collection, certified data erasure, refurbishment, and redistribution services for SMEs and households across Brighton. Devices that remain in good working condition but cannot be upgraded to Windows 11 can be repurposed with Chromebook software. This extends their lifespan, diverts them from landfill, and ensures ongoing security updates are managed by Google. Crucially, refurbished devices are then donated to residents in Brighton and Hove who lack internet access, supporting digital inclusion alongside environmental goals.

By linking sustainability with data security, Tech-Takeback offers a trusted route for circular engagement. Its model reduces e-waste, safeguards privacy, and strengthens community resilience: demonstrating how local initiatives can transform a global challenge into social value for businesses and residents alike.

The Social Value of Re-use

The potential scope of impact is large. Material Focus (2023) estimates that across the UK, about 20 million functional but unused laptops and devices are stored in households and small to medium-sized enterprises. If these devices were donated and reused, they could generate up to £44.7 billion in social value and help millions of people escape digital poverty. These figures not only reflect the environmental benefits of avoided harm and resource recovery but also highlight the wide social advantages of increased connectivity.

Since its inception, Tech-Takeback has prevented over 90 tonnes of technology from entering landfill or incineration, saving 949 tonnes of CO2e (scope 3) emissions and redistributing 46 tonnes of refurbished items to residents. According to Tech-Takeback’s The Social Value of Reuse Report, reusing one laptop resulted in environmental savings of 25.90 kg of CO2 emissions, 126 kg of rare earth materials, and 36.3 m³ of water saved per year; that is enough water for 145,200 cups of tea!

The partnership with the Chartered Institute of Waste Management (CIWM) further increased its impact. A CIWM-funded pilot distributed 60 refurbished laptops to digitally excluded individuals, creating an estimated £258,000 in social value, averaging £4,300 per device.

Behind these figures are people like Oliver*, a Brighton resident who became homeless after an injury forced him out of work. Through Tech-Takeback, he received a refurbished laptop and digital training support:

“My life just fell apart. I was a plasterer, and I didn’t know how to do anything else. This laptop was a blessing. I reconnected with my daughter, completed online training, and got a new job. I’m moving into a new flat tomorrow. I’ll never forget what you did for me, and I wish I could thank the person who donated their laptop. They probably saved my life and they’ll never know.”

*Details and information have been changed.

The redistribution of refurbished laptops is, therefore, more than a charitable act; it is a structural intervention that helps individuals access the internet in a digital world. In Brighton and Hove, this is a pressing local issue: Healthwatch Brighton and Hove (2021) reported that approximately 21% of the city’s population lack adequate internet access. A single device can enable a household to apply for jobs and training, access essential healthcare and housing services, support children with their homework, and reconnect with relatives. When idle devices are redistributed across Brighton and Hove, the benefits go far beyond the device itself. This circular reuse initiative boosts employability, supports mental and physical health, and strengthens community participation.

Policy, Collaboration and Local Action

Realising Brighton and Hove’s circular potential requires coordinated local authority action, corporate engagement, and individual participation. The Circularity Gap Report emphasises the importance of simultaneously reducing virgin material use and scaling reuse. Government policy can create enabling conditions that prioritise repair, refurbishment, and reuse through procurement policies, obsolescence regulation, and waste incentives.

Donating unused devices through Tech-Takeback helps organisations meet these procurement requirements while creating measurable social value. Businesses can also set circularity targets, incorporate reuse into their corporate sustainability strategies, and collaborate with organisations like Tech-Takeback to ensure secure, high-integrity device collection and redistribution.

At the household level, the appeal is clear: by donating unused devices, Brighton and Hove residents turn latent social value into tangible benefits for their digitally excluded neighbours. Referring to Material Focus’s estimate of 20 million devices, even modest rates of donation in cities like Brighton could lead to significant local improvements in connectivity, environmental protection, and social impact.

Conclusion

The circular economy is not just an environmental model; it is a blueprint for societal renewal. Brighton and Hove’s experience with Tech-Takeback shows that circularity can be local, inclusive, and transformative—reducing landfill, conserving resources, and empowering communities. Material Focus’s estimate of 20 million unused devices stored in UK households, alongside the fact that 21% of residents in Brighton and Hove lack adequate internet access, makes the call to action clear: donate, refurbish, and redistribute. By mobilising residents, businesses, and local government to prioritise reuse (through secure collection, refurbishment, and redistribution), Brighton and Hove can become a city where nothing, and no one, is wasted.

_____________

Emily Jones is a Social Value Executive at Tech-Takeback, and a Circular Economy Research Volunteer at Circular Brighton and Hove.

Perspective pieces are the responsibility of the authors, and do not commit Climate:Change in any way. Comments are welcome.