Cheaper Power 2030, Net Zero 2050: The energy debate continues

Joe Tabachnik

Key Points:

The UK government’s Clean Power 2030 plan aims to decarbonise the UK’s power system by 2030 through accelerated deployment of clean energy capacity.

The plan has drawn considerable public scrutiny and cross-party debate, turning clean energy into a politicised issue.

The Tony Blair Institute for Global Change (TBI) is one notable critic, recently releasing a report arguing that Clean Power 2030 is not fit for purpose and risks increasing the cost of electricity, further undermining the competitiveness of the UK’s energy sector.

Professor Sir Dieter Helm has also argued that British energy policy is not cheap, not home-grown and not secure.

There have been some important changes in the UK Budget of November 2025;

All this needs to be unpacked. The review:

Summarises the analysis and seven priorities of Clean Power 2030;

Summarises the analysis and six recommendations of the TBI report;

Highlights the main arguments made by Dieter Helm;

Reviews the changes introduced in the 2025 Budget; and

Introduces six topics for further discussion.

A pdf of the paper can be downloaded here.

1. Introduction

The UK Government’s plan to decarbonise the power sector, Clean Power 2030, has become very controversial. It was reviewed for Climate:Change by Rebecca Tekleysus, here, with a focus on the implications for Brighton and Hove.

On the one hand, proponents argue that the plan will accelerate the transition to a green economy, increase energy security, reduce bills, and create jobs. On the other hand, critics argue that going too fast will increase cost in the short term, and lock already high costs into the system for the foreseeable future. Further, they argue that it will actually increase energy dependency, especially on imports of gas.

Professor Sir Dieter Helm has been a notable critic, arguing that Government policy is ‘baking in very high prices, . . . creating a much more fragile system with ever-greater intermittency, . . . crystalising a reliance on imported energy (electricity, gas and oil), and . . . (forcing) the regulator to commit to doubling the size of the grid to deliver the same output of firm power.’.

The Tony Blair Institute for Global Change has recently taken a careful and systematic look at the issue. Its report, ‘Cheaper Power 2030, Net Zero 2050’, argues strongly that ‘clean electricity is the future of UK energy – for the climate, for national security and for long-term economic strength’. However, it concludes that:

‘The UK’s current energy strategy risks getting the balance wrong. If the transition continues in a way that raises costs, weakens reliability and undermines growth, it will fail both politically and practically. That failure would erode public support at home, damage Britain’s credibility abroad and hand momentum to opponents of climate action.’

All this needs to be unpacked. We do this in five steps:

An introduction to Clean Power 2030;

A review of the TBI Report;

A summary of Dieter Helm on energy;

A summary of changes made in the UK budget 2025; and

A discussion of issues for further debate.

2. An introduction to Clean Power 2030

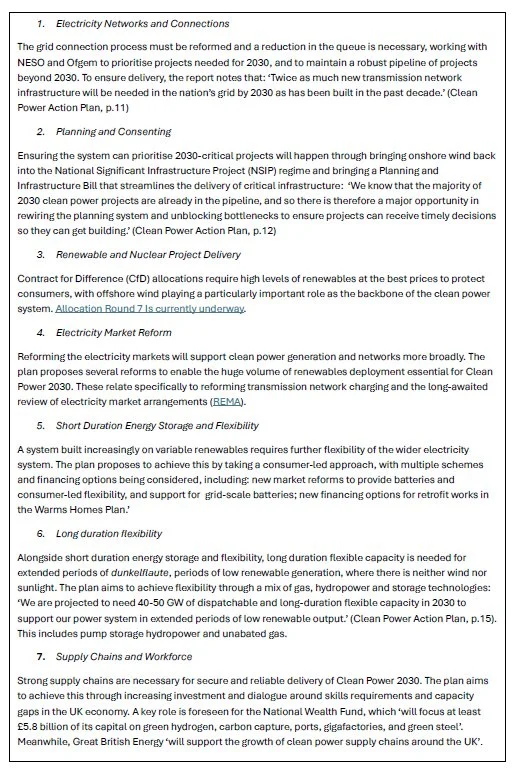

To begin with the The Clean Power 2030 Action Plan. This is the government's plan to decarbonise the UK’s power system. The plan aims for clean sources to produce at least as much power as Great Britain consumes in total by 2030, and at least 95% of Great Britian’s generation. It says that the route to clean power will require mass deployment of wind and solar generation facilities, a fundamental reform of the connections process, an acceleration of clean infrastructure projects through the planning system, and the delivery of projects by the private sector. To achieve these goals, an estimated £40 billion must be spent on average per year between 2025-2030, comprising of £30 billion in generation assets, and £10 billion in transmission network assets. There are seven priorities, summarised in Box 1. As the report notes, all this implies a huge scale-up in low carbon generation: see Figure 1 for a detailed breakdown.

Box 1

Priorities of Clean Power 2030

Source: From NESO Clean Power 2030 Annex 1, p.20

3. The TBI analysis

Understanding British Energy in Recent Decades

The review by the Tony Blair Institute begins by noting three major trends that have characterised the UK energy system. These are:

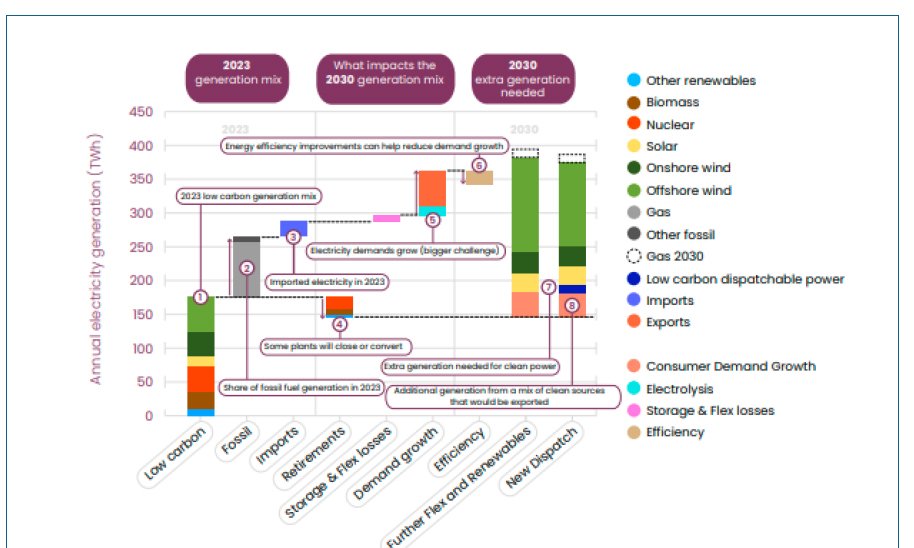

1. The UK’s Shift from Net Energy Exporter to Net Importer;

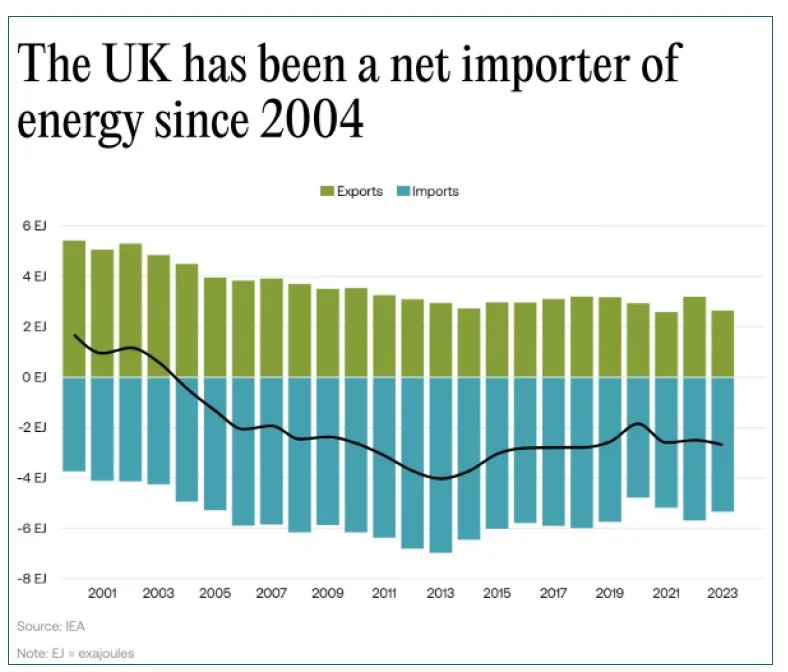

2. A long-term reduction in energy consumption across the economy; and

3. The rapid decarbonisation of electricity supply alongside rising energy costs.

The trends are illustrated in Figures 2-4.

Figure 2

Source: Cheaper Power 2030, Net Zero 2050

Figure 3

Source: Cheaper Power 2030, Net Zero 2050

TBI attribute the change from exporter to importer primarily to a decline in fossil-fuel reserves, with North Sea Production falling 68% since its peak in 1999. A mixture of natural decline, the Energy Profits Levy and pauses on new licences have driven investment away from fossil fuel extraction. Imports have been expensive, in 2023 the UK spent £117 billion on imports, while liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports have grown by 171% between 2018 and 2023 to supplement lower domestic production. This reliance on imported LNG has rendered the UK less energy secure and more vulnerable to higher prices.

The demand reduction largely reflects energy efficiency improvements, as the UK has essentially decoupled growth from energy use. Structural economic change also partially accounts for this change, with the long-term decline of many energy intensive industrial sectors, such as steel and chemicals. However, the report also notes that involuntary cutbacks in response to high prices have driven further reductions in energy consumption. For example, during the 2022 energy crisis, almost 80% of households turned their thermostats to lower temperatures in November and December 2022 compared to the previous year. The price rises saw one in three people plunged into fuel poverty, with one in four choosing not to turn on the heating during winter. The social impact is considerable. Cold homes resulted in 13400 more deaths in the winter period between December 2021 and March 2022 and additional pressure on the NHS.

As to the rise in the price of electricity, the liberalisation of the electricity market and other measures has had a dramatic impact on the generation mix, particularly the rising share of gas (Figure 5) .

Figure 5

Source: Cheaper Power 2030, Net Zero 2050, citing OurWorldInData

Understanding the Price of British Electricity

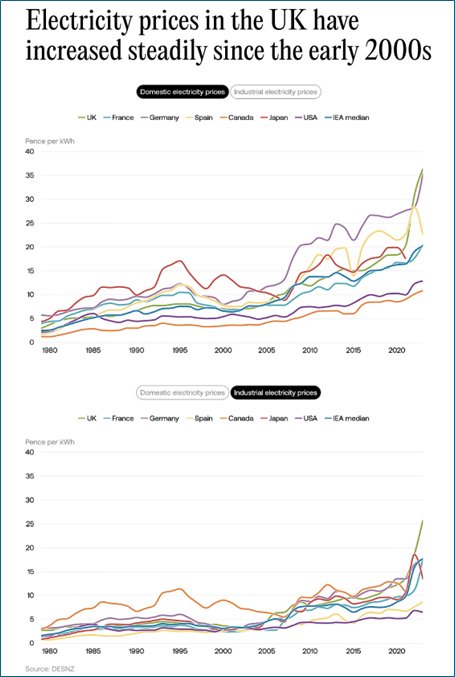

The impact of these changes is significant. TBI argue that electricity prices in the UK are much higher than its peers:

‘In 1990, domestic electricity prices in the UK were just 10 per cent above the International Energy Agency (IEA) median and among the most affordable in the G7. By 2005, they had crept up to 17 per cent above the IEA median. By 2020 . . . they had more than doubled, standing more than 40 per cent above the IEA median. This trend shows that the UK’s relative decline in affordability pre-dated the spike of 2022–23, when prices surged to 64 per cent above the IEA median and the highest in the G7.’ (TBI, p.16).

Before analysing the drivers of higher electricity prices, it is first useful to understand the components of a typical household electricity bill (TBI, p.21):

Wholesale price, usually determined by gas prices, accounts for about one third of the bill

Network costs make up 20%

Current and legacy subsidies account for another 20%

The remainder includes value-added tax, fuel-poverty support schemes, the smart-meter rollout, and supplier costs and margins.

Multiple factors contribute to high electricity prices, TBI choose to highlight the three most impactful causes:

Gas still sets the price

The price of gas was the cause of rapidly rising energy costs after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. As the wholesale price remains the largest component of the electricity bill, the impact of this price increase was particularly large (TBI, p.24).

Whilst gas prices in the UK are largely aligned with Europe, gas sets the wholesale price of electricity in the UK much more frequently. ‘In 2021 natural gas set the UK’s day-ahead marginal electricity price 97% of the time [compared to] an average of 39% … across the EU, Norway and the UK’ (TBI, p.26). Other countries with low carbon grids have a strong backbone of baseload generating sources that frequently set the price, such as nuclear energy in France, or hydroelectric power in Sweden and Norway.

2. Grid and balancing costs are rising

A shift to decentralised, weather dependent renewables require more sophisticated system management and stronger grid infrastructure. Balancing costs are the money spent to keep supply and demand in sync, costs that will inherently increase in a renewables-based system.

TBI argue that the way decarbonisation has been pursued in the UK has rendered these costs higher than necessary. The location of the UK’s best offshore wind resources, in the North Sea and Northern Scotland are far from major demand centres. This build out has not been matched by a coordinated expansion of the transmission grid or storage infrastructure. As a result, constraint payments are required, compensating wind farms to turn off when the grid cannot absorb their input, and paying gas turbines to run in their place. Constraint payments reached £1.7 billion in 2024-25, and are projected to peak between £4-8 billion in 2030. Additionally, demand side flexibilities are underdeveloped to shift consumption, placing further constraints on the supply side and increasing system costs. NESO estimates that balancing costs will rise from £2.4 billion in 2023-24 to £4.7 billion by 2030 (TBI, p.30).

3. Levies are increasing

The subsidies component of the bill has increased dramatically, from 8.5% in 2015 to 20% today (TBI, p.31). Many early renewables policies adopted in the UK were expensive and long-lasting. For example, while the Renewables Obligation closed to new projects in 2017, payments to existing projects will continue until 2037. Some Feed-in-Tariff payments will continue until 2044.

Finally, new schemes are also emerging with substantial levy-backed costs. Carbon capture and storage (CCS) will be primarily funded through electricity levies, adding long-term upward pressure on electricity prices. The building of new nuclear could be added to this list.

Creating a UK Energy Strategy for Now and for the Future

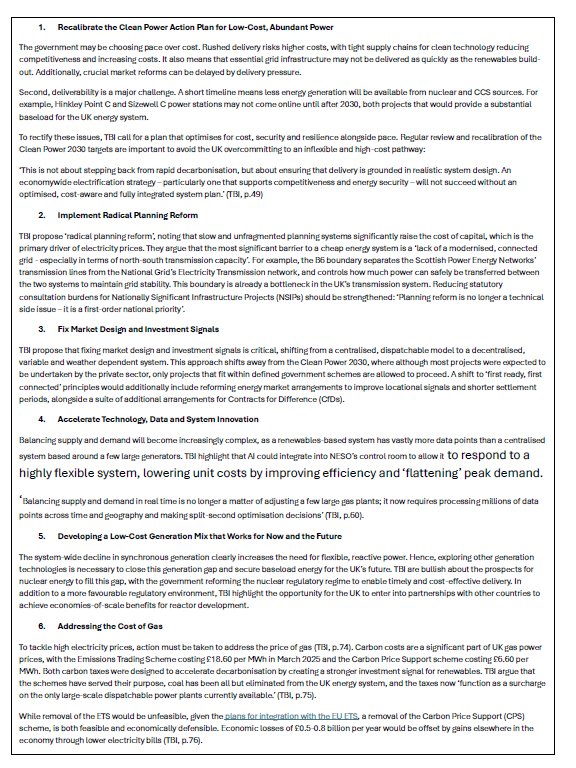

TBI argue that the context of energy as an increasingly desirable economic input, a central security concern, and falling international climate cooperation render the Clean Power 2030 plan no longer fit for purpose as it risks the UK missing out on the industrial and technological rewards of the transition. An alternative framing is suggested: ‘Cheaper Power 2030, Net Zero 2050’. There are six priorities, summarised in Box 2. These are:

1. Recalibrating the UK’s clean-power plan for least-cost pathways;

2. Fixing market design and investment signals;

3. Implementing radical planning reform;

4. Accelerating technology, data and system innovation;

5. Developing a low-cost generation mix that works for now and the future; and

6. Making gas cheaper

Box 2

Priority recommendations of the TBI Report

4. Helm on Energy

Professor Sir Dieter Helm covers similar territory to the TBI report. His headline is ‘British energy policy – not cheap, not home-grown and not secure’. He argues for two categories of changes, largely mirroring the reforms presented in the TBI report:

1. Taking costs onto the government’s –and ultimately the taxpayers’ – account; and

2. Slowing down or stopping signing yet more CfDs, and notably radically cutting back on AR7.

Helm also makes three more brief points about the future energy system of the UK that closely mirror the concerns presented by TBI:

Hard Choices in Nuclear

Helm notes that since the Hinkley CfD and Sizewell C RAB contracts are now locked in, the choice with nuclear is about further PWRs and the SMR programme. The design of these programmes is crucial for the future of nuclear in the UK.

A Serious Plan for Gas

On a similar line to TBI, a serious plan for gas is necessary for future energy prices and security in an intermittent renewables-dominated system. One option, different to the recommendations of TBI, is building a strategic gas reserve.

Carbon Prices

Helm differs from TBI slightly on carbon prices, arguing that ‘simply removing carbon prices in Britain will cause serious issues to arise.’ Whilst both reports agree that the removal of the ETS is likely difficult, Helm is generally more pro-carbon price noting that ‘The carbon price has the merit of being a key (and, in resource costs, cheapest) way of signalling to those with the lowest costs of reducing their emissions’.

5. UK Budget 2025: Impacts on Energy Policy

The recent UK budget had several impacts on energy policy, and the government’s Clean Power 2030 plans. For all climate-related announcements, see CarbonBrief’s report. In total, the policy changes are projected to cut bills by £134 for the typical household.

ECO abolished

The Energy Company Obligation (ECO), a scheme which obliged energy suppliers to promote measures that ‘improve the ability of low-income, fuel-poor and vulnerable households to heat their homes’ (Ofgem). The scheme was hit with a number of scandals, with design failures resulting in ‘widespread issues with the quality of installations’. However, not all commentators welcome its removal. E3G, an independent climate change think tank, are particularly critical of the government’s scrapping of ECO: ‘By axing it, the Treasury has removed the main programme to provide a long-term solution to fuel poverty and one of the most important schemes for reducing the cost of power infrastructure in the future.’.

Renewables Obligation partially moved to general taxation

The Renewables Obligation, a scheme designed to encourage the generation of electricity from renewable sources in the UK, has been partially moved onto general taxation. The scheme was introduced in 2002, when procurement of renewable energy was significantly more expensive, and ended in 2017. Because all consumers paid the same levy through energy bills, the scheme was regressive. 75% of the levy has been moved onto general taxation to reduce immediate energy costs for consumers and to introduce a fairer funding mechanism.

Sizewell levy added to bills

The government also announced their decision to invest £14.2 billion in Sizewell C under a Regulated Asset Base (RAB) model, allowing the costs of building the plant to be partially recovered from consumers during construction. This involves an additional charge on consumer energy bills to support the cost of development, generating £0.7 billion in 2026-2027, doubling to £1.4 billion by 2030-2031.

EV mileage charge

Finally, the introduction of a 3p per mile road charge for electric vehicles from April 2028, and 1.5p per mile for plug-in hybrid cars. This charge is designed to help maintain road infrastructure, in anticipation of falling fuel-duty receipts as more cars become electric. The tax is expected to raise approximately £1.1bn in 2028-29 and £1.9bn in 2030-31.

6. Further questions for UK Energy Policy

TBI’s recommendations are developed with grounded evidence and a solid base of assumptions. Its analysis involves rigorous modelling, actionable policy steps, and a balance of ambition and practicality. However, there are several questions about the future of UK energy policy that are worth exploring further:

How fast to go?

First, TBI note that the UK’s impact on global climate is marginal, accounting for just 0.81% of global emissions in 2023. Whilst they acknowledge the UK’s earlier large share of emissions, citing the IPCC’s first report in 1990, where the share was 2.65%, they do not engage with ideas that historical emissions may be present responsibility. Historically, the UK is the fifth largest emitter, accounting for 4.4% of global cumulative emissions.

It is certainly true that further UK decarbonisation will have a marginal impact compared to decarbonisation efforts in bigger emitting countries, but this does not absolve the UK from further efforts. Furthermore, the UK has firmly established itself as a climate leader since the establishment of the Climate Change Act 2008. Therefore, reaching a clean energy grid sooner, albeit at a higher cost, could re-establish the UK as a climate leader.

Which policies, and in what order?

The question of policy sequencing is central. Transitioning to a cheaper, flexible, decentralised and market-based system cannot happen overnight, and careful consideration must be given to not just how policies are implemented, but when.

For example, TBI advocate for reforms to the CfD system for the current AR7 auctions. They also wish to introduce measures to lower the cost of gas. Questions remain about how quickly these reforms will happen, and how to ensure consistent private sector investments in these changing environments. Does private investment happen sooner, in anticipation of reforms that may reduce long-term cost risks, or does uncertainty around the timing of these changes delay capital deployment?

Poor sequencing could result in a mismatch, where reforms arrive too late to support investment decisions already taken, or where investors wait for clarity, slowing down the very deployment needed to deliver system-wide benefits. Therefore, careful attention must be given to future policy sequencing to drive the investment, price and decarbonisation benefits that TBI are hoping to achieve.

What about community energy?

TBI’s paper lacked a discussion of the potential of community energy. Community energy groups raise capital locally and install manage and maintain renewable energy assets. For example, Brighton and Hove Energy Services Cooperative (BHESCo) manages 25 projects within the Brighton and Hove area. These projects install renewable energy, with maintenance and installation costs recouped through electricity payments at below-market rates. BHESCo maintain a strong social mission, with surplus energy used to provide a benefit to local communities. The main challenge facing community energy has been scaling up, an area where the government could provide considerable support.

What is the role of the state in energy policy?

Two further contentious questions arise regarding the role of the state in energy policy. The first focuses on risk, namely, how to balance decentralisation and system vulnerability. The second is a wider question about state and market control and how different models of the energy system can deliver benefits to wider society.

On risk, it is trickly to reconcile TBI’s pro-decentralisation approach with their arguments for energy security and the wider social implications. Britian’s long-term energy security no-doubt depends on an economy based on clean electricity, reducing the demand for fossil fuel imports. The paper acknowledges that this shift comes with several challenges, such as an increased reliance on imported materials and technologies or increased opportunities for cyber-attacks in a digitalised system. However, TBI’s approach of further decentralisation could create further risks for energy security through increased system vulnerabilities and reduced government oversight. To ensure their plans would result in increased energy security, further research is required on how to reduce system vulnerabilities across a system with less government oversight, and more nodes.

On state control, keeping energy assets under public control can be beneficial for the public as long term security and economic viabilities issues are all more likely to be considered by a public body than a profit-first private sector supplier. The recent creation of Great British Energy (GBE), a new publicly owned clean-energy company aims to invest in, develop and own clean energy generation and storage projects across the UK. It is a vehicle designed to deliver tangible benefits to local communities, in a way that the private sector may not. It has an explicit remit to support locally owned generation.

One example of a country where energy has primarily remained under state control for energy security and community benefit reasons is Sweden. Major generators and the transmission system are state-owned, giving the government tools to manage system security, and focus on system capacity and public objectives rather than shareholder returns. Additionally, many cities own their own energy companies, reinvesting surpluses locally and strengthening local energy resilience.

What technical challenges remain for grid security and operational efficiency?

TBI are bullish about the integration and development of a suite of technologies designed to improve power generation and grid operational efficiency. However, their recommendations often rest on unproven technologies that are yet to have a large-scale impact on the energy sector.

Integrating nuclear and renewable technologies can be tricky. Nuclear is proposed as a low-carbon baseload generator with a stabilising force on energy costs. Spain is one such case that proves balancing renewables with energy is complex. Spain’s generation comprised of 38.4% nuclear and 31.1% renewables in 2024. Spanish grid operators have found that a combination of renewables and nuclear can cause further instability, as the system lacks enough fast, flexible balancing capacity. Nuclear power is inflexible by nature, and whilst Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) may offer improvements, there are no operational examples of SMRs dynamically paired with renewables.

In the AI boom, it is easy to overstate its current use-cases. While it seems feasible that AI will create opportunities for balancing energy, there is currently limited evidence that AI can achieve this at scale. China has recently unveiled a plan to integrate AI into its energy sector, aiming to create advanced mechanisms for forecasting, grid balancing and planning by 2030. How these projects will play out is up for debate, but they will prove key indicators for whether AI can be integrated into the energy system on a large scale.

Finally, the report does not sufficiently consider the technical challenges of the ‘last mile’ low voltage (LV) networks that power UK households. The report focuses on generation and transmission costs, with little discussion of distribution constraints. Limitations of LV networks are one of the most significant bottlenecks to large-scale household electrification. For example, studies by Distribution Network Operators (DNOs) have indicated that only 30-50% of homes in suburban and urban contexts could adopt heat pumps without reinforcement. A focus on distribution, transmission, and electrification without adequate attention to LV networks may result in aggregate peak demand exceeding the networks’ rated capacity, leading to voltage drops, thermal overloading and more frequent outages. Reinforcement of the LV networks to address these challenges is planned but costly. Investment is projected to rise from ~£5 billion (RIIO-ED1) to £20–25 billion in the RIIO-ED2 period (2023–2028) to accommodate these changes. Further research into these investments is required to ensure that delivery is carried out in a cheap and efficient manner.

To what extent does the public support Clean Power 2030, and how does the budget impact their goals?

While TBI recognise the implementation of some of their recommendations may be challenging, the current political environment renders many of the recommendations almost impossible. For example, the removal of the Carbon Price Support (CPS) tax may be economically defensible but would be politically challenging. Given the recent tax raises in the Budget, the removal of the CPS levy would be challenging as it would likely cost the government around £0.5 billion to £0.8 billion per year in lost revenue and associated impacts. In a time of tax rises and climate commitments, this does not seem like a politically feasible option.

Public support for renewable energy is high with 80% of people supporting the use of renewable energy. However, with only 41% of people expecting renewable energy to decrease bills over the long-term, more work must be done to convince to public that renewables can deliver cheaper, cleaner power. Additionally, the impacts of Clean Power 2030 on welfare are yet to be realised. Much of the public’s support for the plan may rest on its distributional effects.

The recent budget, whilst not directly changing the goals of Clean Power 2030, will undoubtedly have several implications for electricity demand and the government’s ability to deliver their plan. The bid to lower energy bills, through the scrapping of ECO and the shifting of 75% of the Renewables Obligation into general taxation effectively improve the price of electricity relative to gas, potentially increasing electricity demand in some areas. The EV charge will likely have the opposite effect, making it more expensive for drivers to choose electric, although EV running costs will remain much cheaper than combustion equivalents. The Sizewell C levy is perhaps the most significant step forward for Clean Power 2030 in the budget, demonstrating the government’s commitment to delivering nuclear energy as a core aspect of the UK energy system.

7. Conclusion

This blog has sought to give an overview of recent debates surrounding the UK government’s Clean Power 2030 Action Plan. Focusing on the arguments presented in TBI’s Cheaper Power 2030 report has highlighted the UK’s need for a cleaner, more secure and more affordable energy system. Energy policy is an incredibly complex topic, and getting the balance right will determine whether the UK enters the 2030s with a resilient, affordable clean power system or remains locked into high costs and fragile infrastructure.

____________

Joe Tabachnik holds an MSc in Climate Change, Development and Policy from the Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex.

Perspective pieces are the responsibility of the authors, and do not commit Climate:Change in any way. Comments are welcome.