Heat and the Sea: The Warning in the Waves

Andrew Coleman

Key points:

Britain’s southern waters are undergoing a dramatic transformation caused by climate change, with higher temperatures and marine heatwaves impacting every link in the marine food chain. Kelp forests, seagrass meadows, rocky shores, epipelagic waters, salt marshes, cold water corals, and estuaries are all at risk.

In addition to ecological effects, and the impact on livelihoods, there are also risks to human health, including: increased exposure to harmful algal blooms; jellyfish proliferation; and water quality and pollution.

The Government is missing targets to protect and restore the marine environment.

Locally, there are initiatives, including the Sussex Bay Project, the Sussex Kelp Recovery Project, Weald to Waves, and the Sussex Nature Recovery Strategy.

In order to mitigate the clear impacts of climate change on marine life, and potential impacts on human health, we should look to:

Expand and enforce marine protected areas—with meaningful restrictions on destructive activities.

Embed marine climate risks in planning—ensure adaptation is a requirement in coastal development, restoration, and licensing.

Accelerate restoration projects—such as kelp and oyster bed recovery, which rebuild biodiversity and store carbon.

Invest in early warning and monitoring—deploy local temperature buoys and community science for rapid response.

Strengthen water quality regulations—reduce pollution and nutrient runoff to curb potential increase of algal blooms.

Ensure strategic oversight of the entire marine environment, including in devolution plans.

Introduction

This paper deals specifically with the impact of rising sea temperature on marine life, focusing on Brighton and Hove. Sea level rise and the impact of storms are dealt with elsewhere.

It is worth noting at the outset that the City Council’s legal regulatory remit only extends to the mean low water mark. However, the accelerating pace of marine climate impacts increasingly blurs land‑sea governance boundaries, suggesting the need for joint strategic planning that transcends current statutory limits.

Heat at Our Doorstep

Britain’s southern waters are undergoing a transformation that is as dramatic as it is swift. Off Brighton, sea surface temperatures in 2025 sat more than 3°C above the long‑term seasonal average — a heat anomaly that would once have been headline-making, but is rapidly becoming the norm.

Recent years have seen the combined effect of greenhouse gas emissions, changing ocean currents, and phenomena like El Niño, push global and UK coastal waters to new extremes. In 2024, southern English waters reached some of their highest recorded temperatures, impacting every link in the marine food chain.

The implications run far deeper than the summer swimming season. Warming seas disturb the food chains that underpin our fisheries, degrade blue‑carbon habitats like kelp and seagrass, alter storm patterns and flood risks, and threaten the coastal assets — from ports to promenades — that underpin Brighton and Hove’s economy, culture and way of life. For the people who live, work and play by the sea, this is not a distant projection — it is a lived reality.

Globally, the science tells a consistent story: the oceans are warming, and marine heatwaves are increasing in intensity, frequency, and geographical spread. International science from the EU, UN and IPCC warns of cascading impacts: loss of biodiversity, declining fisheries, and heightened risks to food security, health, and coastal economies. A summary of the evidence can be found in Appendix 1, available as a pdf here.

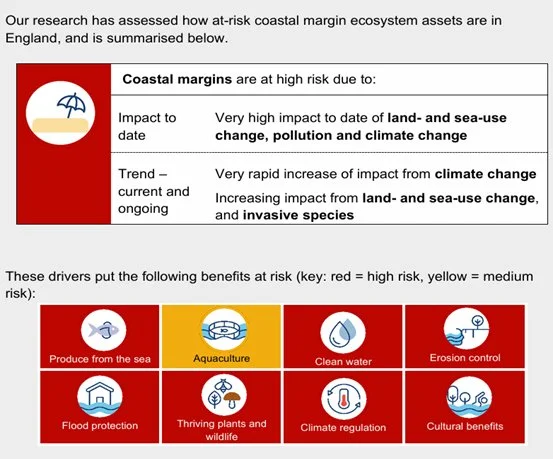

Nationally, the UK’s coastal ecosystems are already shifting (Figure 1 and Appendix 2 (available as a pdf here)). The risks and losses are significant, but it is important to note that there will be ‘winners’ as well as ‘losers’. For example, species like some rays and basking sharks are expected to gain suitable habitat. Native Oysters, which have seen 95% decline in UK populations since the mid-19th century, are expected to see a doubling of suitable habitat.

Figure 1

Assessment of risks to coastal marine margins in England

Source: https://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/publication/6683489974616064

The type of ecosystems that we are most concerned with on the south coast of England (kelp forests, seagrass meadows, rocky shores, epipelagic waters, salt marshes, cold water corals, and estuaries) are predicted to be affected by ‘significant and widespread impacts / risks’. Brighton and Hove Council’s 2024 Climate Risk and Vulnerability Report assessed risks to marine species, habitats and fisheries from changing climatic conditions, including ocean acidification and higher water temperatures, as ‘moderate’ currently, but ‘major’ by the 2080s.

The Sussex Bay 2025 Blueprint, an initiative led by Adur and Worthing Councils, refers to the impacts of climate change on marine life, including:

Increasing sea temperatures / marine heatwaves due to climate change which can stress kelp (which also sequesters carbon and is the subject of the Sussex Kelp Recovery Project);

Rising temperatures and changing ocean currents can affect oxygen levels;

Rising sea temperatures and ocean acidification, both linked to climate change, can weaken shellfish shells, reduce growth rates, and affect the nutritional (and carbon) content of oysters and blue mussels;

Rising sea temperatures can shift the distribution of commercial fish species, potentially leading to declines in local populations; and

Rising sea temperatures and ocean acidification harm species which colonise seabed substrates.

The large kelp beds that were once offshore have already declined hugely – see Figure 2. Kelp provides multiple ecosystem services – perhaps the most important being fish nursery and a carbon ‘sink’.

Fig 2

Extent of Sussex Kelp beds, 1980s-2019

Source: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02421-y

In addition to ecological impacts, there are specific human health challenges for coastal communities.

Increased Exposure to Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs): Warmer waters create favourable conditions for algal blooms, which can produce toxins harmful to swimmers, surfers, and shellfish consumers. Although HABs are currently rare in English coastal waters, rising temperatures and nutrient runoff from urban and agricultural sources may increase their frequency, potentially leading to beach closures, respiratory irritation, and shellfish safety concerns.

Jellyfish Proliferation: Species like the mauve stinger jellyfish are becoming more common off the Sussex coast during warmer months. Stings can cause painful skin reactions, limiting safe recreational swimming and affecting water-based tourism and sports activities popular in Brighton. There is some evidence that some stinging jellyfish may move northwards, but reproduction may be reduced by shorter, warmer winters.

Water Quality and Pollution Risks: More intense summer rainfall events, driven by climate change, increase stormwater runoff and the risk of sewer overflows in the local area. This can lead to temporary spikes in coastal pollution levels, compromising water quality and increasing exposure to microbial hazards for beachgoers, despite increasing pressure on water companies to reduce use of storm outfalls.

Despite these risks, local populations are increasingly turning to the sea for recreation and wellbeing. Sea swimming groups in Brighton and Hove, for example, have grown substantially, reflecting the recognized mental and physical health benefits of ‘blue spaces.’ Continued monitoring and public communication about marine hazards—such as real-time water quality alerts and jellyfish forecasts—are essential to safeguard community health, while supporting safe enjoyment of the UK's unique marine environment.

The policy framework

The Government’s 25 Year Environment Plan contains targets for delivering environmental gain, including in marine areas. These include:

reversing the loss of marine biodiversity and, where practicable, restoring it;

increasing the proportion of protected and well-managed seas; and

better managing existing protected sites.

The Marine Management Organisation (MMO) has the statutory role of marine planning and issuing licences for activities in England’s seas. It has marine spatial plans in place for the whole coastline, including that off the coast of Brighton and Hove. Objective 7 of the South Marine Plan is : ‘ To support the reduction of the environmental, social and economic impacts of climate change, through encouraging the implementation of mitigation and adaptation measures that:

avoid proposals’ indirect contributions to greenhouse gas emissions;

reduce vulnerability;

improve resilience to climate and coastal change; and

consider habitats that provide related ecosystem services.’

However, the Office for Environmental Protection (OEP) has urged government to ‘speed up action in the marine environment’, noting missed commitments such as banning all damaging activities in Marine Protected Areas by 2024.

The UK is unlikely to meet legal obligations for Good Environmental Status. This conclusion probably led the OEP in January 2025 to start an investigation into Defra’s suspected failure to achieve good ecological status of marine waters. The investigation is ongoing, and Defra is consulting on a revised Marine Strategy, which does include an assessment of the impacts of climate change on the indicator species and habitats.

As noted, the Council’s legal regulatory remit only extends to the mean low water mark, so perhaps the limited references to marine impacts are understandable. However, the accelerating pace of marine climate impacts increasingly blurs land‑sea governance boundaries, suggesting the need for joint strategic planning that transcends current statutory limits.

Local initiatives

The Sussex Bay project states that it ‘is a community-born project which is raising funds, ambitions and hopes to rebuild Sussex’s healthy blue ecosystem, for the benefit of our people, our places and our natural environment’. Sussex Bay is commissioning research into seascape restoration, attracting funding for projects, and encouraging and enabling collaboration between relevant parties and communities.

Sussex Bay also supports the Sussex Kelp Recovery Project (SKRP), which ‘was formed to champion, study and facilitate the return of kelp, through progressive, coherent and collaborative action.’ The SKRP is conducting research to establish baseline knowledge of offshore ecology and co-commissioned a Blue Marine Foundation report that investigated the optimum conditions for the restoration of kelp beds.

The introduction in 2021 by the Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority of the Sussex Nearshore Trawling Byelaw banned seafloor bottom trawling within 4 km of the shoreline,. It was hailed by the Sussex Wildlife Trust as ‘a landmark for marine recovery, giving kelp forests, fish nurseries and seabirds a chance to rebound’.

However, these initiatives - as well as others, such as Weald to Waves - are uncoordinated by any oversight body. Governance and community involvement varies hugely. Although there is potential for a new Sussex strategic authority stepping into this role - Sussex Bay and the UN Biosphere were referred to in the response submitted by BHCC to the Government as examples where co-ordination would be useful (despite there being no indication that its remit would extend beyond low water) - this would also potentially remove decision-making further from local stakeholders.

There is already an emerging pan-Sussex Local Nature Recovery Strategy (LNRS), which helpfully includes inshore marine areas (on a voluntary basis – there is no legal requirement to do so). Coastal habitats have been identified as one of the priority habitats in Sussex for action for nature recovery, although marine habitats have not. It is essential that the impacts of climate change on marine habitats and species are considered, and Natural England has published a manual that provides guidance on this.

Choices and trade-offs

Efforts to safeguard Sussex’s coastal waters from the impacts of rising sea temperatures and marine heatwaves are gathering pace, but they carry real-world trade‑offs for local communities and industries.

For example, recorded stakeholder feedback shows that local fishing groups are concerned about the speed, scope, and sequencing of restrictions. In the Sussex Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority (IFCA) meeting minutes of March 2023, members of the Brighton Fishermen’s Society argued that management should ‘allow seasonal flexibility in quotas’ to reflect the fact that species such as bass and mackerel are shifting their range with warming waters. Fishermen have also raised the risk that restricting access in Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) can displace effort to other grounds — potentially increasing pressure on unprotected stock.

Local government faces its own balancing act. Brighton & Hove City Council consultation responses on the City Plan Review (2024) include submissions from marine tourism operators warning that ‘blanket prohibitions’ on certain coastal activities could deter investment in leisure infrastructure. At the same time, council planning officers are obliged to integrate Biodiversity Net Gain requirements into a context where implementation rates are still low in coastal habitats.

Conclusion

In order to mitigate the clear impacts of climate change on marine life, and potential impacts on human health, we should look to:

Expand and enforce marine protected areas—with meaningful restrictions on destructive activities.

Embed marine climate risks in planning—ensure adaptation is a requirement in coastal development, restoration, and licensing.

Accelerate restoration projects—such as kelp and oyster bed recovery, which rebuild biodiversity and store carbon.

Invest in early warning and monitoring—deploy local temperature buoys and community science for rapid response.

Strengthen water quality regulations—reduce pollution and nutrient runoff to curb potential increase of algal blooms.

Ensure strategic oversight of the entire marine environment, including in devolution plans.

The Sussex Kelp Recovery Project offers an example of inclusive decision-making. Here, management measures were co-designed, adaptive fishing methods trialled, and socio-economic benefits tracked alongside ecological gains. This demonstrates that where competing priorities are openly acknowledged and addressed, it is possible to align ecological resilience with community livelihoods.

The challenge now is to apply such participatory and adaptive approaches more widely: phasing in restrictions with targeted transition support, using real-time monitoring to refine MPA boundaries as ecosystems shift, and ensuring that those most affected have a meaningful voice in governance.

_________

Andrew Coleman is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Applied Sciences at the University of Brighton

Perspective pieces are the responsibility of the authors, and do not commit Climate:Change in any way. Comments are welcome.