Meeting Report: Overcoming the Barriers to Community Energy in Brighton and Hove

Key points

This was a specialist round-table on Overcoming the Barriers to Community Energy in Brighton and Hove. There were five background papers, covering different aspects of regulatory regimes, Government programmes, and financing, available here.

Community Energy offers a ‘Hands-Off’ model, in which, typically, Community Energy Groups raise equity locally, then take responsibility for installation, management, maintenance and insurance of renewable energy infrastructure, recouping the cost by charging domestic and non-domestic customers a below-market price for electricity – and simultaneously contributing to social programmes. Brighton and Hove has been strongly supportive of community energy projects in its decarbonisation strategy.

There is an urgent need to scale Community Energy, without losing the USP which is the social benefit and the scope for community wealth-building.

The constraints to scale arise from national policy uncertainties, motivation and behavioural issues, problems with financial and contractual models, local authority funding and administrative constraints, and uncertainty associated with rapid technical change.

Many practical changes can be considered, in the domains of motivation and behaviour change, working with landlords, new financial models, and new partnerships with the Council.

A strong network is being developed on community energy in Brighton and Hove to take the practical suggestions forward.

If you are interested in a 12 minute AI podcast about this event, courtesy of Google’s NotebookLM, you will find it here. It was obtained by uploading pdfs of this report and the five Background Notes. We don’t guarantee every last detail of the content, but it is a lively and impressive product. The podcast will download to your Download folder.

A specialist round-table was held on 7 October 2025 on ‘Overcoming the Barriers to Community Energy in Brighton and Hove’. The event was organised jointly by the two energy co-operatives based in Brighton and Hove, the Brighton Energy Cooperative and Brighton and Hove Energy Services Co-operative, along with Climate:Change, an independent think-tank. About 35 people attended, a mixture of energy specialists, property managers and policy-makers. There were five background papers, covering different aspects of regulatory regimes, Government programmes, and financing (Figure 1); they are available here.

Figure 1

Community Energy Background Notes

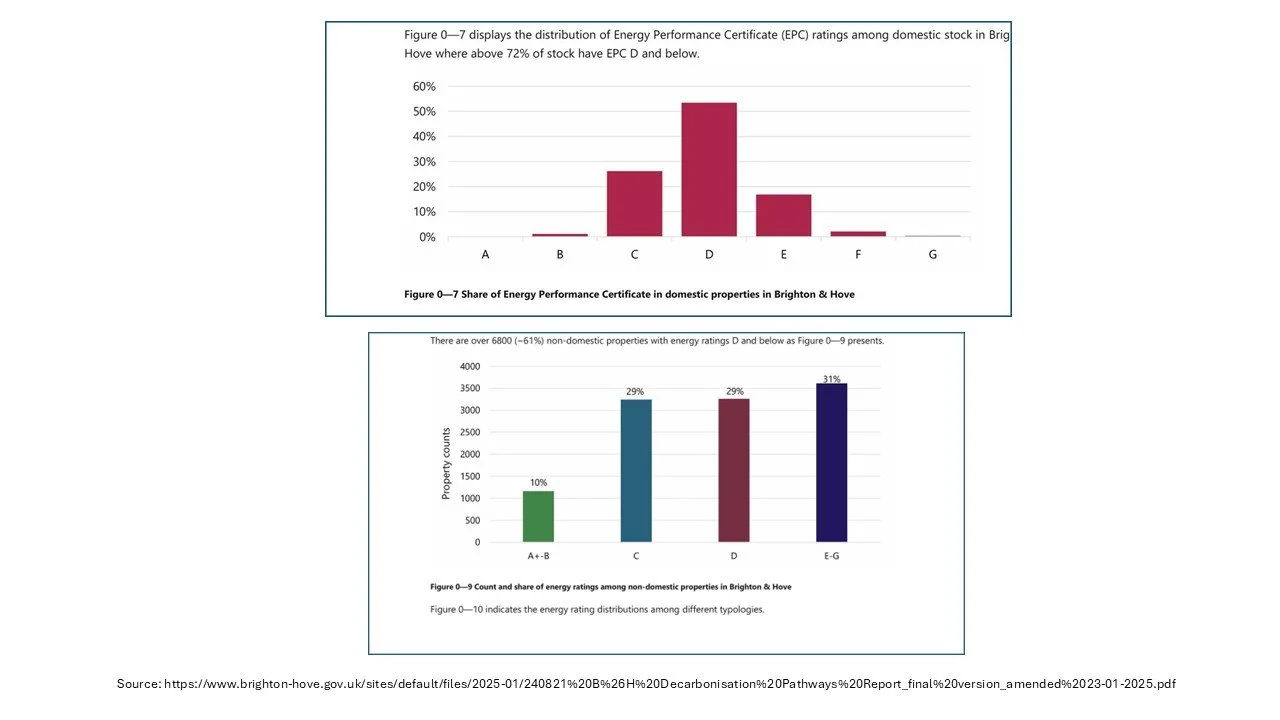

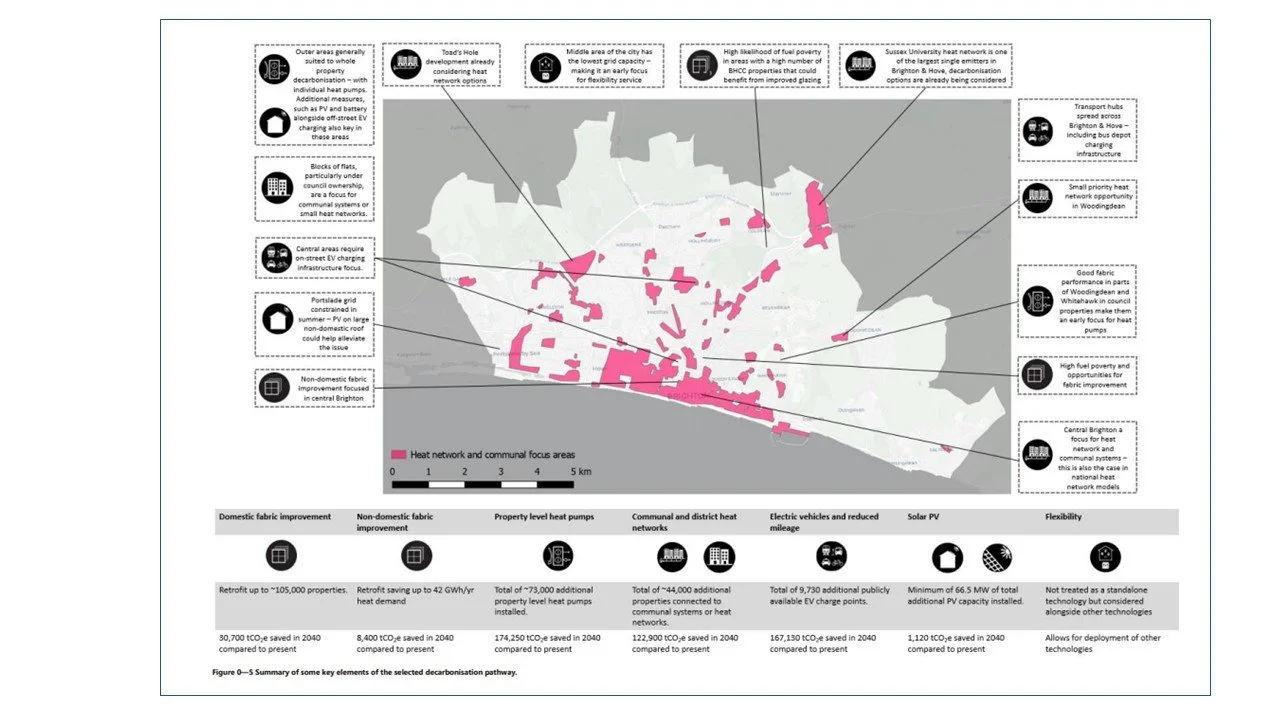

Introducing the meeting, Simon Maxwell, Co-Chair of Climate:Change, provided some background information on EPC ratings of domestic and non-domestic buildings in the City, illustrating the high number of properties rating D or below (Figure 2). There were many reasons to consider renewable energy investments, including savings on energy bills and warmer homes, as well as making a contribution to reduced emissions. It was important to understand the role that community energy could play in the transition, and to identify how the barriers to expansion of the sector could be tackled. Simon noted that the Brighton and Hove Decarbonisation Pathways study was enthusiastic about the role of community energy and offered many possibilities, domestic, non-domestic and neighbourhood- or district-based (Figure 3).

Figure 2

EPC rating of domestic and non-domestic building in Brighton and Hove

Figure 3

Brighton and Hove Decarbonisation Pathways Study: Key Priorities and Opportunities

There followed presentations by the two energy coops, and by Community Energy England:

Kayla Ente spoke for BHESCO. She emphasised the social mission of community energy, with equity often raised locally, and with surpluses used to provide a benefit to local communities. The funding model used by BHESCO, with domestic and non-domestic partners, involved no payment upfront, with installation and maintenance costs recouped via payments for electricity (at below market rates); there were now 25 projects under management. Kayla emphasised the benefits of the model to households and businesses; for landlords, installing renewable energy could help raise EPC levels, meeting new standards in the process, and make properties more attractive to rent. The big challenge was to accelerate and go to greater scale. This could well involve partnering with commercial funders, though maintaining the strong social mission. Kayla showed a video illustrating BHESCO’s work with the Fabrica gallery in Brighton – here.

Atlanta Cook and Matt Brown spoke for BEC. Their work focused on solar installations for non-domestic properties, now with 60 partners. The funding model and social impact were similar to other community energy initiatives. On the generation side, it could be understood as ‘Hands-Off Commercial Solar’, with BEC taking responsibility for installation, management, maintenance and insurance. On the social side, there was a guaranteed community benefit, amounting to 3% of revenue, which could be thought of as ‘paying forward’ through a community fund. For example, BEC funded educational programmes in schools. Availability of funding was not the problem; rather, BEC had observed that commercial property owners were not easy to connect with, and often not motivated or incentivised to take up renewable energy options. This was the major constraint to scaling up. Atlanta and Matt showed a video about their work, here.

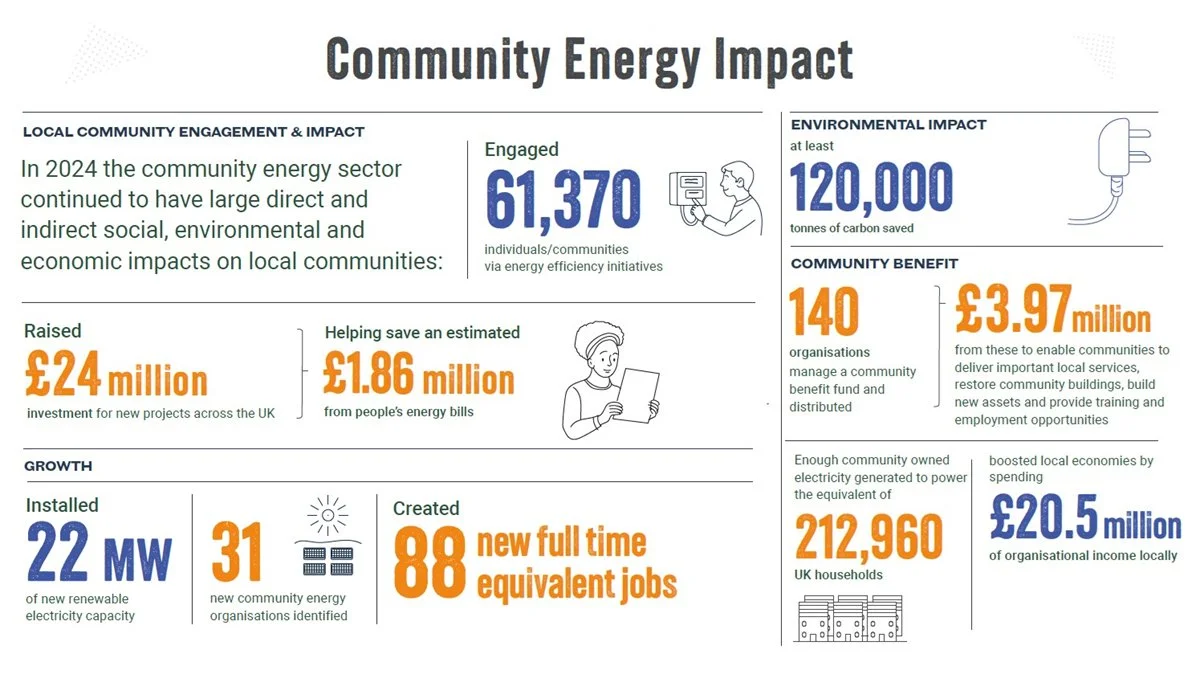

John Taylor spoke for Community Energy England. He emphasised the current scale of community energy programmes in England, with 22 MW of renewable energy installed in the last year; the total installed capacity of 400MW was bigger than most commercial suppliers. John laid special stress on the social benefits of community energy: 140 organisations managed a community fund, distributing nearly £4m for local projects (Figure 4). There was also great benefit in people seeing their savings invested in local infrastructure – also keeping money flowing in their local community. The construction of local micro-grids could make communities less dependent on the national grid, leading to both financial savings and greater energy security. All this resulted in community wealth-building, and greatly strengthened public support for new infrastructure. For the future, John encouraged community energy organisations to exploit the unmet need on rooftops, but also to support new forms of infrastructure, like solar panels on carports, and solar plus wind on open land. He emphasised that the framework was evolving, from a narrow focus on electricity generation, to a broader concern with electricity use, including for heat pumps and EV charging.

Figure 4

The impact of community energy programmes

Participants recognised the many social, environmental and economic benefits of community energy, and the urgent need for greater scale. The social benefit and the scope for community wealth-building were recognised as the distinctive Unique Selling Point (USP) of community energy. The race to scale might well involve commercial funders and new partnerships, but should not dilute this essential element.

From barriers . . .

The meeting then turned to understanding the barriers to the growth of the sector. The discussion ranged from national to local, and across policy arenas, from regulation to behaviour change. Among the key points made were the following:

National policy

Policy uncertainty, with regard to future energy prices, but also possibly the regulatory environment (especially with regard to EPC standards and large company carbon reporting requirements);

Complexities related to management of the grid limiting the spread of local energy projects (for example, the Balance of Settlements Code, and the requirement for local community suppliers of energy to be licensed operators);

The possible impact of devolution;

Motivation and behaviour change

Fear of the unknown;

A general reluctance of landlords to innovate, especially if investments benefited tenants only;

Financial and administrative models

Need for scale in commercial installations;

The complexity of long-term contractual models on offer, especially in an era of rapidly fluctuating electricity prices;

It was noted that community energy projects involving households were quite time-consuming to set up, not least in shared buildings like blocks of flats, where many stakeholders had to sign off;

Benefit-sharing: getting the right balance between low prices for consumers and securing enough funds for community benefit;

High transactions costs of community energy;

Competition from commercial suppliers (without community benefit)

Local constraints

In Brighton and Hove, the high number of rented properties (see point (a) above), and also the high number of listed buildings;

Financial constraints but also administrative procedures in the Council (for example, having to pay for individual licences);

Technological issues

Fast changing technology which might make investments obsolete or conversely make the investment case stronger (for example, being able to use car batteries to feed the grid);

. . to solutions

What, then, were the solutions? The meeting focused on four areas: incentivising behaviour change; working with landlords; financial and contractual models; and new partnerships with the Council.

With regard to motivation and behaviour change, the suggestion was to adopt the EAST model: changes should be Easy, Affordable, Social, and Timely. A marketing campaign focused on these four aspects could support scale-up, with social benefit as the key USP for community energy. Community involvement would create social contagion. ‘Take Back Control’ was suggested as a slogan for local community projects and micro-grids. New partners could be found to offer financial incentives to potential participants (for example, roofers could offer free solar installation).

On working with landlords, the Hands-off Commercial Solar approach was intuitively attractive, especially when combined with community benefit. In addition to more and better marketing, there were two key approaches. One was regulation (‘just make it illegal not to install renewable energy’). The other was to look again at the financial model and increase the incentives for landlords. Both were worth pursuing, though neither was straightforward. The regulation option might be at risk if net zero continued to be contested politically. The incentives option was potentially a prisoner of the diminishing gap between the commercial price of electricity and what community energy companies needed to charge in order to cover costs: there just might not be the margin needed to keep prices lower than market rates for customers, while simultaneously delivering a social benefit. There were other options, building on the ‘social’ leg of the behaviour change model: could there be recognition for progressive landlords (for example those on a B-Corps certification pathway).

On financial models, it seemed that the availability of start-up funding was not a major constraint, by raising community equity or loans. Locally based community energy projects had popular economic and social benefits that were easy to de couple from contentious and negative net zero climate framings. However establishing viable business models to attract and de risk these investments was complicated (as noted above). The development of SMART technology was viewed as offering opportunities, However, there were issues of national policy to keep under review (especially the electricity price and export tariffs to the grid). It would also be helpful to simplify contractual models, especially for households who might balk at 25-year commitments. For commercial landlords, there needed to be sufficient savings to be worthwhile in the context of overall income from property.

On working with the Council, there was great willingness on both sides to develop new partnership models. Could the Council simplify and standardise contracts? Should the Council offer business rate relief to those installing renewable energy? Should the Council endorse the community energy companies and publicise their efforts? Could there be a one-stop shop to provide information about warm home schemes? Could the Council be helped to raise money from central Government schemes, like ECO? Was there potential to develop a group funding model, like the one used in Bristol? Were there new models that could be tried in social housing? All these were worth exploring, though it was important to understand the financial and headcount constraints the Council faced. Any project that reduced income or cost money would be very difficult to pursue.

Summarising the discussion, Simon Maxwell said there were many practical steps that could be taken. The social benefit of community energy was a valuable characteristic of the model, both in raising money and in the sense of ownership. For customers, especially commercial landlords, there needed to be an irresistible financial case; that perhaps needed to be clarified. It would be important to be fully briefed on changes to electricity pricing in particular. Regulation also had great potential, taking due account of political pitfalls ahead. Partnership with the Council would be invaluable. He emphasised that change happened when three things came together: political leadership; public support; and the power of a good idea. Political leadership had not been much discussed in the meeting, and would continue to be needed locally.

The meeting ended with agreement that there were still some knotty problems to solve, so there was more to do. However, the network of those interested in community energy had been strengthened, and there was enthusiasm to work together in the future.

_________

Simon Maxwell

We acknowledge financial support for this event from the Brighton Energy Cooperative.