Thinking about heat pumps

Andrew Barnett

Key points

Heat pumps are a central component of the UK’s and Brighton’s pathway to net zero.

Adoption is growing, but is still way behind target – and way behind adoption in other European countries.

The reasons for slow adoption include the cost of installation and the high price of electricity, as well as a shortage of qualified installers.

Our survey confirms these problems are also present in Brighton and Hove.

Additional problems in the City are the high proportion of flats, rented properties and listed buildings, all of which present challenges to the roll-out of heat pumps.

Inequality and poverty also constrain adoption in the City: households in energy poverty are unable to pay the capital cost of a heat pump.

One solution to this problem is provided by the Energy Company Obligation, which mandates energy companies to pay for households to reduce emissions and save on energy bills -this could be used much more widely in Brighton and Hove.

There are many other opportunities to accelerate the installation of heat pumps in the City. Some of these need national policy action (e.g. on electricity prices or regulations requiring landlords to act). Others can be implemented locally. The Council could: strengthen its role as a source of trusted information; publish information on its own experience of installing heat pumps in Council properties; and support innovative community-based financing models such as Pay as You Save.

The Problem

Heat pumps are a central component of the UK’s and Brighton’s pathway to net zero. Heat pumps provide domestic heating by extracting heat from the air or ground in greater amounts than the energy in the electricity used to power the machine. When electricity is generated from renewable sources, the net carbon emissions are substantially lower than from gas central heating.

The UK government aims to see 600,000 heat pumps installed annually by 2028. But in 2022, only 55,000 heat pumps were sold. However, the government grant for heat pumps was raised from £5,000 to £7,500 in October 2023 and since then the demand has picked up, with a growth of 63% in 2024. The latest annual progress report of the Climate Change Committee reports that 98,000 heat pumps were installed in 2024.

The adoption rate of heat pumps is about 400 per 100,000 population in the UK, compared to 3,000 in Europe. France had the largest heat pump sales in Europe at 621,776 units (compared to 55,000 in the UK). 60% of households in Norway have heat pumps.

The reasons for the UK’s poor performance have been summarised in a recent report by House of Commons Public Accounts Committee. First, there is the cost, as the average cost of a heat pump is currently £11,600, four times the cost of a new gas boiler. The committee was concerned that most households receiving the government’s £7,500 Boiler Upgrade Scheme grant might be from more affluent groups, and might well have bought the equipment without a grant.

Second, ‘heat pumps are also more expensive to run than boilers, because of the cost of electricity being higher than gas’. The committee notes that the price ratio between the cost of electricity and gas is currently 4:1, one of the highest in Europe. Part of the reason is the government levying a large proportion of the environmental costs of the energy transition on electricity rather than gas bills. 16% of electricity bills are due to these levies, while levies are only 5% on gas bills.

The government is currently planning to rebalance the cost of energy, but notes that it is both economically and politically complex. Furthermore, there are currently strong pressures to raise the cost of electricity to pay for £24bn grid investment.

A more restrictive policy option was reported recently as being mulled by Ed Miliband's Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ), which would reduce energy bills for heat pump owners. The move would involve shifting green levies — the policy costs used to pay for other green schemes — off the electricity bills of heat pump owners. However, such a policy may not be politically acceptable given levels of energy poverty, as such a policy will involve subsiding people who are already rich enough to invest in heat pumps.

DESNZ provides a comparison of UK electricity prices with those in Europe. Comparing the EU14 and UK, average domestic electricity prices in the last six months of 2024 were the highest in Germany (including taxes & levies and accounting for subsidies), with the UK as the 4th Highest. In 2017 the purchasing power correction for domestic electricity, showed that UK prices were the eleventh highest on a £/kWh basis but the seventh lowest on a PPS/kWh basis. For domestic electricity, the UK prices were the eleventh highest on a £/kWh basis but the seventh lowest on a PPS/kWh basis.

In practice, these average costs of electricity are probably less relevant in the heat pump market as customers can get substantial discounts on their tariffs if they have heat pumps or electric vehicles. For instance, owners of electric vehicles can currently obtain electricity at night at 7p/kWh.

More generally, the Public Accounts Committee was concerned that there is too much complexity and potential confusion for households to enable them to make informed decisions about installing a heat pump. Households can face complex decisions when looking to install a heat pump. For instance, households were unclear if they had to meet certain insulation standards before they were able to obtain grants under the Boiler Upgrade Scheme. DESNZ is removing minimum standards for loft and cavity wall insulation as a precondition for a heat pump grant. But the committee notes that the department has not made available any additional evidence about how this choice will impact on energy bills.

The committee felt that the DESNZ has made good progress in increasing the number of trained heat pump installers, but it faces a huge challenge to make sure there are enough installers to achieve its target to install 600,000 heat pumps per year by 2028. DESNZ reported that it is on track towards meeting its target to have 12,000 trained heat pump installers by 2025, with 7,000 installers trained so far.

What is the situation in Brighton and Hove?

The national picture is mirrored in Brighton and Hove. The Climate:Change Briefing Paper on energy noted how few heat pumps were installed in the city, with only 221 installed in the 14 years to September 2023, although the Council’s consultants suggest the figure could now be as high as 1,100.

It was thought useful to ask members of the Climate:Change mailing list what their opinion was about heat pumps and to explore the specific conditions in Brighton through a small qualitative questionnaire.

Results of a survey

Seventeen people responded, and 13 agreed to be interviewed by phone. Nine people had heat pumps, while 4 had explored the possibility but decided not to invest. Of the users, most were enthusiastic and were very pleased with their investment, though two had only recently installed the equipment and did not have much operational experience. One respondent had a complete failure and the equipment now stands abandoned in her garden. This user was an earlier adopter, and had her pump installed about ten years ago. The house ‘never felt warm’, but three years ago the machine started to cut out and was replaced by a gas boiler. This installation was presumably an early type of pump with a relatively low output temperature. There also appear to have been problems with the thermostat and controllers. The installer moved away and maintenance appears to have been a problem at times.

Few users kept a record of the financial saving. But one respondent kept detailed records (he is an energy advisor). He calculated that when using Octopus’s ‘cosy tariff’, he is saving £505 a year on his total heating costs from his installation of the pump, in part because he is able to use his solar electricity to run the pump. But comparing his current set up (pump, solar, battery), compared to a base case of a gas boiler and no solar he saves about £1860 per year.

BHCC provide useful links to information about heat pumps, together with their capital and running costs.

The respondents presented an interesting paradox. All users were keen to ‘do the right thing’ for the environment, and probably would have installed their pumps regardless of the cost (though all liked the £7,500 subsidy). Of those that did not invest, most found the cost too expensive even with the subsidy. One respondent felt she could not afford the £2,000 price tag. Other users stated that the cost of their investments ranged from £2,000, to over £20,000, presumably as a result of differing house sizes, designs, and the amount of installation work involved (including new pipe work and radiators).

Of those that did not invest, the majority found that their properties were judged unsuitable. In one case, the home was a flat and had insufficient access for the contractors. Octopus energy were reported to be good, but very selective in the premises they agree to install renewable equipment. One respondent was told their property was too big, but they found another contractor who successfully completed the work (in addition Octopus do not install solar panels on flat roofs). Heat Geeks were also mentioned favourably.

Another non-investor found that the location of the pump was unsatisfactory, as it would have been on a patio outside a French window. Another non-user felt the pipe and other installation work was ‘too much of a hassle’. Almost all the users were surprised at the amount of work involved in installing the water tanks and pipe work, but were happy to accept it as a necessary task.

Perhaps the most surprising response was that one user was able to obtain a 100% grant for his pump. This appeared to be a special “Green Home” grant available during covid.

One respondent was part of the Visit My Heat Pump scheme. This is an effective scheme, as many people have said that they adopted heat pumps only after visiting neighbours who have one. Another adopter said she bought her heat pump after speaking to an existing owner who gave a talk at a Hanover Action meeting.

An important point was raised by a non-adopter who said she would wait until the technology ‘stabilised’. People often decide not to invest during periods of rapid technical change as they believe that they will get a better product (and a lower price) if they wait.

The survey generally supports many of the ideas developed in the Climate:Change Briefing Paper on Behaviour Change. It also confirms that installers are now more plentiful than they were and do a good job. But it also underlines the concern that many properties in Brighton and Hove are judged unsuitable for heat pumps, often because they are too large.

It is also clear that flats may also present a problem. While not an inherent feature of flats, one respondent provided correspondence that alleged that a housing development in Rottingdean had severe problems with heat pumps. It was not possible to get the full details of the problem, nor how it has been resolved, but one of the issues was said to be that after the air source heat pumps were installed, the developers realised that they could not heat both water and radiators. So, they installed radiators that plug into a regular electric socket which is proving to be very expensive.

The people who benefit most from heat pumps appear to be those that also have access to the cheap electricity tariffs available to people with electric vehicle chargers and those with storage batteries (and possibly solar panels). This suggests that there is an optimal (though expensive) sequence of investments for those that ‘want to do the right thing’ in terms of personally reaching net zero: start by retro-fitting insulation, move on to an electric vehicle (to obtain the lowest electricity tariff), then install photo voltaic panels and a battery to help drive the heat pump, before finally installing a heat pump.

Leave no one behind

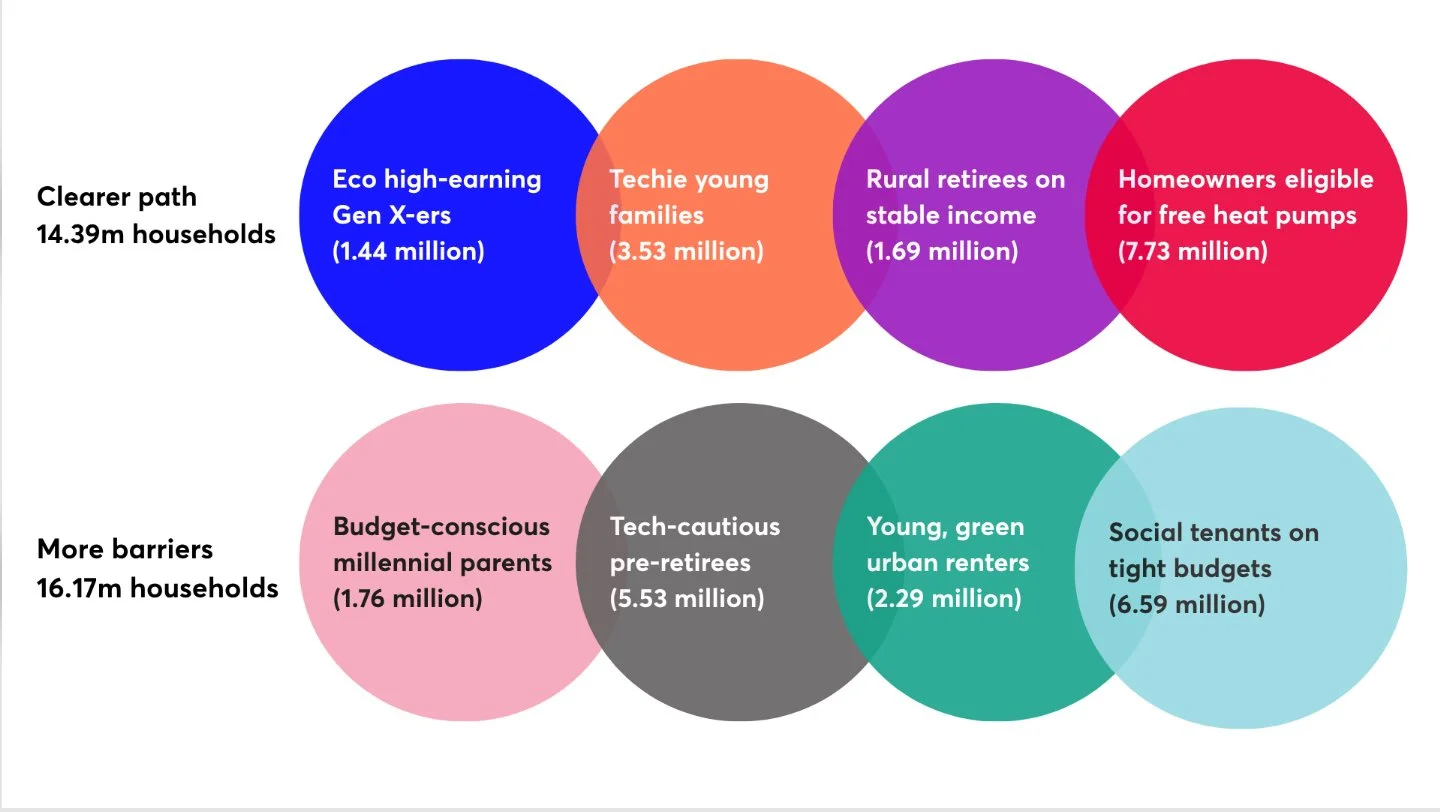

Nesta has produced a useful segmentation of the market for heat pumps (Figure 1). It suggests that 14 million households belong to household types with a clear path to adoption, while 16 million do not. While this suggests there is still a large potential market for heat pumps, it also indicates four categories of the population that will face barriers to adoption.

Figure 1

The segmentation of the market for heat pumps

Source: https://www.nesta.org.uk/feature/targeting-heat-pumps-eight-key-consumer-audiences-july25/

This situation is reflected in the data for Brighton and Hove There is the considerable energy poverty in the city. While Brighton & Hove has a growing qualified and prosperous core, it is also one of the UK’s most unequal cities. This means that there are significant areas of very low energy consumption because, in effect, of extensive energy poverty. Any effective carbon reduction plan will have to take equity and inclusion seriously. The areas of the City with the “best” (ie lowest) carbon emissions footprint are those that consume the least energy. These include areas identified by the Office for National Statistics as 'Cosmopolitan student neighbourhoods' in Moulsecoomb and Bevendean, 'Households in terraces and flats' in Hollingdean and Stanmer, and 'Cosmopolitan student neighbourhoods' in St. Peter's and North Laine. The ‘worst’ areas for carbon emissions are the 'Affluent communities' in Hove Park, 'Highly qualified professionals' in Wish ward, and 'Highly qualified professionals' in Preston Park ward.

There is probably a disincentive for landlords to invest in heat pumps as they incur the costs, but the tenants receive the benefits. While this is not an insurmountable problem, this seems to be a problem for Brighton and Hove as the City has a significantly higher percentage of residents renting (38.2%) compared with the South East (26.1%) and England & Wales (31%).

The recent House of Commons Public Accounts Committee report mentioned earlier also draws attention to concerns about energy poverty and the reliance on private households investing their own money in heat pumps. But it is surprising that there is no mention in the report (or indeed elsewhere) of the Energy Company Obligation (ECO), which is specifically designed to provide grants to upgrade the least insulated houses and provide renewable energy options.

The Energy Company Obligation

The Energy Company Obligation Phase 4 (ECO4) is a government initiative running from 27 July 2022 31 March 2026. It is aimed at reducing fuel poverty and carbon emissions for poorer households. Energy suppliers are mandated to fund energy-saving measures for qualifying households, including: Air Source Heat Pumps, loft and cavity wall insulation, solid wall insulation, first-time central heating systems, solar panels, and high-efficiency boilers. Installation is completed free of charge by Certified Engineers. These upgrades are designed to improve the home's Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating, leading to lower energy bills and a more comfortable living environment. The scheme is implemented by companies such as UKEM.

ECO4 sets its objectives in terms of energy, requiring suppliers to achieve a total of £224.3 million in annual bill savings for domestic premises by 31 March 2026. This is called the Home Heating Cost Reduction Obligation (HHCRO). The objective in terms of required investments is not specified. According to OFGEM, since the launch of the scheme to the end of March 2025, 49,136 low-carbon heating systems have been supported. Of these 97% were air source heat pumps.

According to ECO Energy Systems, ‘despite the tremendous success of ECO4, some rumours about ECO4 grants still exist’. According to this source, ECO4 has made significant progress since its launch: initially, 50,000 homes received energy upgrades under ECO4. It results in 200,000 tons reduction in carbon emissions. Additionally, households that participated in the scheme saw an average savings of £300 on their annual energy bills in 2022. By 2023, 25,000 more homes benefited from heating upgrades, and a total 300,000 tons of carbon emission was reduced. The average savings per household also rose, up to £350. Last year, a total of 265,000 ECO measures were installed. These numbers were 60% higher than in 2022.

Strangely, although ECO4 is publicised on the BHCC website, this programme does not appear to have been used by BHCC. According to BHCC’s office of Sustainability and Energy Homes and Investment, BHCC ‘haven’t used ECO funding for any of the installs on our own housing stock’ (personal communication, currently being clarified further). BHCC do not keep information on the number of heat pumps installed under this programme, nor is City level data provided by Ofgem. The vast majority of ECO grants in the City are likely to be a private arrangement between the householder and the energy supplier/installer. OFGEM do not appear to publish data on the uptake of the Boiler Upgrade Scheme at the level of Brighton and Hove city.

In addition to grants, a number of local organisations are creating highly innovative financing options, such as BHESCO’s ‘pay as you save’ financing model. BHESCo’s unique financing initiative enables property owners to pay for the cost of energy upgrades with the savings they achieve on their monthly energy bill. BHESCO designs the new energy project, pays for the cost of the installation, and then recoups that cost over a number of years from the customer, who makes instant savings on their bill.

Conclusions

The literature and qualitative survey of heat pump users in Brighton confirms that heat pumps are effective if properly designed and installed. The number of installations and installers is improving. None-the-less, heat pumps remain relatively expensive to buy and run. Policies to increase the number of installations, such as lowering the cost of electricity relative to gas, or increasing the grant element are outside the control of the local authority (though local electricity suppliers can and do offer cheaper tariffs).

But the fact remains that large parts of Brighton are unlikely to invest in heat pumps: Brighton and Hove has a large proportion of rented accommodation, there are large numbers of flats, and great number of people in energy poverty. It might be possible to introduce regulations requiring landlords to install heat pumps, but this may well reduce the amount of rented accommodation in the city, and is anyway likely to require a decision at the national level.

But the question then remains, what if anything can BHCC do to improve the rate of implementation of heat pumps? At the heart of the problem appears to be that potential adopters do not know who they can trust to get information about the cost and performance of heat pumps. Installers do appear to be improving, but the field often appears complex and property-specific. Furthermore, the uncertainty facing potential private investors is increased by the current confusions and contradictions in the national policy space, especially about the relative cost of gas and electricity discussed earlier.

The council could invest in building the necessary trust to advise the public on heat pumps. It could also promote the ECO4 heat pump grant scheme. One way of gaining such trust would be to publicise the results of BHCC’s independent evaluations or audits of their own net zero investments on domestic accommodation, which was announced in 2021:

‘As well as solar panels, we’re reviewing heating systems and starting to install other forms of low carbon heating in council homes. We’ve already installed over 20 air source heat pumps, which reduce emissions and lower energy bills. There are plans to install up to 100 more air source heat pumps this year (2022-23), focusing on homes with inefficient electric heating and lower energy efficiency ratings. And we’re carrying out an options appraisal which will see 265 flats in blocks in north Whitehawk move from gas to low carbon heating and hot water over the next 2 to 3 years. The project will significantly reduce carbon emissions and give residents greater control over the heating and hot water in their home.’

It is currently unclear (personal communication with a Councillor) if this data was in fact gathered, but independent evidence of real experience could help enhance the City’s credibility as a reliable source of information for potential investors and might also convince gas fitters to promote heat pumps.

_____

Image: https://www.nesta.org.uk/feature/targeting-heat-pumps-eight-key-consumer-audiences-july25/

Andrew Barnett leads on energy for Climate:Change

Perspective pieces are the responsibility of the authors, and do not commit Climate:Change in any way. Guest posts are published to explore issues or stimulate debate. Comments are welcome.